Staking Claim to Entitlements under MGNREGA . How can Women Make Their Demands?

-

From

CGIAR Initiative on Gender Equality

-

Published on

03.12.24

- Impact Area

Reposted here with permission from The India Forum. Originally published at: The India Forum

By Kalyani Raghunathan, Katrina Kosec, Jordan Kyle, Sudha Narayanan, and Soumyajit Ray

“What will I do by going there?”, answered Phoolan Devi from Bolangir district of Odisha, when asked if she attended the palli (revenue village) sabha. The answer seemed obvious – “Nothing.” After all, it was her husband who took all important decisions at home. But in Odisha, deliberations about assets to be constructed under India’s large national workfare programme, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), typically take place in palli sabha meetings. It is here that women like Phoolan Devi can stake a claim to assets that would be useful to them or their families. Yet, most of them do not. What can drive women to exercise that right in ways that benefit themselves and their families?

Many public sector programmes—like MGNREGA—provide entitlements that can provide women with critical resources and improve their livelihoods. Yet, to “claim” these entitlements, citizens must take actions like filing paperwork, attending and speaking up in public meetings, participating in community planning processes, or approaching officials and community leaders. To take these actions, citizens need to both aspire to claim entitlements and be capable of doing so (Kruks-Wisner 2018). While claim-making aspirations reflect beliefs about self-efficacy (or ability to effect change) and about whether the state can and will respond to claims, claim-making capabilities reflect the knowledge and skills which individuals need to make a claim on the state. For example, beneficiaries need to know about the programme and how to complete the formal or informal processes required of them, have access to the relevant functionaries, be willing and able to advocate for themselves, and have the ability to navigate and participate in public spaces.

In many respects, women are at a disadvantage relative to men in claim-making. Women routinely face normative and structural barriers that are likely to limit both their aspirations and their capabilities for claim-making. For example, they often have less mobility, lower knowledge about public programmes, diminished access to assets and decision-making in their homes, lower literacy, and less-developed public speaking skills (Kosec et al., 2024).

If women are systematically less likely to engage in active claim-making, MGNREGA will be unable to benefit women to its full potential.

Within MGNREGA, which provides 100 days of work on demand at a stipulated minimum wage and aims to build durable assets through that work, the selection of assets is meant to be participatory. In theory, bottom-up, participatory planning should yield assets that are relevant and valued by the community, contributing to local well-being and livelihoods. Yet, whether MGNREGA can do so depends on who participates within the planning process. If women are systematically less likely to engage in active claim-making, MGNREGA will be unable to benefit women to its full potential.

To understand contextual factors around women’s claim-making within MGNREGA, we conducted a mixed methods study in Odisha including both a large-scale quantitative survey of 3,426 women across 230 gram panchayats (GPs) in five districts (Ganjam, Kalahandi, Mayurbhanj, Bolangir, and Rayagada) and an in-depth qualitative study including both men and women from six GPs in three districts. All women in our quantitative survey are MGNREGA job card holders and thus part of the key population that the programme intends to include within the participatory asset selection process. Ideally, women working on MGNREGA job sites should be contributing their ideas on what should be built that could most benefit them and their communities.

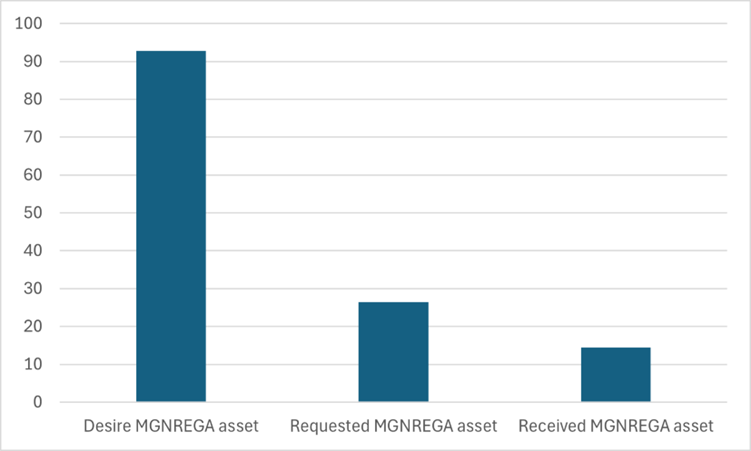

Our quantitative survey showed a significant gap between those who wish they had demanded an asset and those who have ever done so. While 92.8% of women desire an MGNREGA asset, only 26.4% have ever requested one, either individually or as part of a group (Figure 1). Even fewer have been successful in their claims. High demand for MGNREGA assets corresponds with other research which has found that an overwhelming 90% of those who have received assets through the programme find them useful (Ranaware et al. 2015).

Figure 1: Asset demands and successful claims

With such a significant gap between women’s aspirations and their active claim-making,

understanding the contextual factors that explain why and when women are likely to make these active demands is critical for ensuring MGNREGA can better deliver benefits for women going forward.

Assets under MGNREGA

The MGNREGA was rolled out in rural areas in three phases between 2006 and 2008 and provides 100 days of unskilled manual work per year at stipulated minimum wages to any rural household that requests it. The programme provided 2.4 billion person-days of work in 2023-24 and received an allocation of Rs 860 billion in the recently released annual Union budget for 2024-25, making it the largest workfare programme in the world.

The programme uses its resources to primarily focus on building rural assets that can serve as the basis for sustainable livelihoods. A pre-approved list of 262 eligible assets is considered, which fall under natural resource management, individual and community assets, rural infrastructure, and common infrastructure for women’s groups. Individual assets are privately owned and built on private lands. Community assets can be public goods, like rural roads for connectivity, or closer to “club goods”, where non-members can be excluded, such as farm ponds for aquaculture leased to and managed by women’s self-help groups (SHGs).

In theory, communities have wide latitude both to recommend which types of assets—whether individual or community, rural infrastructure or natural resource management, and so on—would be most beneficial and to deliberate among the various demands within the gram sabha. Despite the large range of possibilities and the potential these assets have to transform communities and livelihoods, for many, the MGNREGA continues to be viewed as a source of income for days worked, not a pathway to achieve sustainable and remunerative livelihoods. As one woman we spoke to put it, “I do not know that one can demand assets under MGNREGA. I only know about this scheme as I sometimes worked as labourer (…) and got paid 150-200 rupees daily in cash.”

Notably, from a rights perspective, the Act envisions a participatory deliberative process for the selection of assets and their beneficiaries. On Gandhi Jayanti, October 2 each year, a village-level meeting or gram sabha, is to be held in every village, marking the start of the asset planning process. In Odisha, a series of ward or revenue-village meetings follow, where community members can raise their demands for assets. These demands are then placed before the gram sabha for deliberation by the community, and the list of works for that village agreed upon in a special village townhall meeting held early the next calendar year. Technical estimates of the materials needed, and the number of workdays required are drawn up and a “shelf of works” created.

Many ways of making claims: Qualitative analysis

Although MGNREGA spells out a process for requesting assets and deliberating which ones should ultimately be constructed, our research revealed that there are several informal processes in addition to the formal ones through which decisions around assets are made. These range from “top-down” – households being informed that they have been selected as the recipients of an asset – to those that rely on social networks, to more participatory approaches – such as women discussing asset requests with their SHG and placing a collective request. This is consistent with other research in India, which emphasizes the role of informal brokers and processes playing important roles in coordinating development requests from the state (Auerbach 2019; Kruks-Wisner 2018).

Even when asset demands are made and discussed within gram sabhas, villages vary widely in how gram sabha deliberations are conducted, what is discussed, and how inclusive those discussions are (Sanyal and Rao 2019). It follows, therefore, that the choice of assets to be built and of who will benefit from those assets depends crucially on power dynamics within communities and the inclusivity of decision-making. Our qualitative interviews indicate several possible ways of making claims, both formal and informal, though these differ across men and women. Some men report attending the palli sabha meetings to raise demands. Damodar from Bolangir, for example, gets information on the meetings from the ward member and he is a regular attendee. Others approach village functionaries directly. Ajit was told about cashew plantations by the udyan mitra, staff from the horticulture department, and then went to the GP office to register his demand. Madan from Ganjam used his own connections; the agricultural officer happened to be a resident of his relative’s village, so he approached the officer directly at a block level meeting.

Though few women we interviewed found personal success in ‘palli sabha’ meetings, many credited their SHG leadership for successful claim-making on their behalf—often not requiring them to personally attend a ‘palli sabha’ meeting.

For women, these formal channels are often much more formidable. Often, women do not know when and where palli sabha meetings are being held, and when they do, they are not always able to attend. A woman in Ganjam said she did not know much about the palli sabha or gram sabha meetings; her husband attends, but domestic responsibilities prevent her from traveling. Another woman from Bolangir said her husband attends the palli sabha without her; when she expressed her interest in attending, her husband resisted. Other women are aware of meetings, but do not attend due to internal barriers and social norms—such as doubts about what they would do, how they would be regarded, or whether they would have any real influence.

Some women do attend the meetings but struggle to voice their demands publicly. “I feel a little bit shy of saying something there [at the palli sabha]. I am uneducated and always worry that I might say something wrong,” said Janaki Devi, who received a community water tank. Janaki Devi rarely attends these meetings, reporting that they are male-dominated, and women do not participate actively. Contrary to the spirit of the MGNREGA, the community water tank she received was simply announced by the sarpanch, or village head.

Though few women we interviewed found personal success in palli sabha meetings, many credited their SHG leadership for successful claim-making on their behalf—often not requiring them to personally attend a palli sabha meeting. For example, Phoolan Devi got a mango plantation because an official visited her SHG—though she was not precisely aware of how the process unfolded. Jigya Devi similarly received a nutri-garden by asking via her panchayat SHG madam, who helped her with the documents required for submission—whilst flagging that she never attends palli sabha meetings, only SHG meetings. Thus, speaking in SHGs and advocating with SHG leadership can be a substitute for engaging formally with local leaders and MGNREGA functionaries.

Many stories documenting these varying pathways to obtaining MGNREGA assets are documented in this video that highlights instances where women in Odisha have successfully obtained assets. READ MORE

The authors are with The International Food Policy Research Institute.

Note from the authors: Respondent’s names have been changed to protect their identities. This work is part of an ongoing study into women’s voice and agency in the MGNREGA asset selection process. Readers can access our paper on claim-making here. Based on these initial results, we designed an information leaflet, an inspirational video, and a skills training manual that we delivered to close to 8000 women in the same districts. The causal impact evaluation for that study is pre-registered here, and we will share results when available.

Related news

-

Justice in Transition: CGIAR Climate Security Launches Climate Justice Research at INAET 2025

The Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)15.04.25-

Climate adaptation & mitigation

From energy geopolitics to climate equity, this year’s International Network on African Energy Tra…

Read more -

-

ASEAN-CGIAR Program charts future course, emphasizing scalability and sustainability

CGIAR15.04.25-

Adaptation

-

Climate adaptation & mitigation

-

Environmental health & biodiversity

-

Food security

-

Mitigation

-

Nutrition

-

Nutrition, health & food security

Bangkok, Thailand - The ASEAN-CGIAR Innovate for Food and Nutrition Security Regional Program recent…

Read more -

-

Building Capacity in Crop Modeling to Advance Circular Food Systems in Southern Africa

International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)10.04.25-

Big data

-

Climate adaptation & mitigation

Training Equips Researchers to Support Smallholder Farmers with Climate-Smart, Sustainable Agricultu…

Read more -