Pathways to power in fragile settings: rethinking women’s roles in agriculture and food systems

-

From

Food Frontiers and Security Science Program

-

Published on

29.04.25

- Impact Area

A women fills a water vessel from a underground rainwater harvesting tank in the Thar Desert near Phalodi, India. Photo Credit: Dieter Telemans/Panos Pictures

By Agnes Quisumbing, Jordan Kyle, Katrina Kosec, and Catherine Ragasa

Research shows that women play pivotal roles in farming—across value chains, and in food systems as a whole. With harmful effects of climate change, conflict, forced migration, and other problems on the rise, many women around the world find themselves in increasingly fragile settings—creating new challenges in efforts to achieve gender equity and empowerment in food systems.

An IFPRI-organized March 13 session at the NGO Forum on the 69th Commission on the Status of Women at United Nations Headquarters in New York highlighted recent research on different aspects of how women in fragile food systems can become empowered. Evidence shows that when equipped with tools, voice, and recognition, women act—not only to improve their own well-being but to strengthen resilience across households and communities.

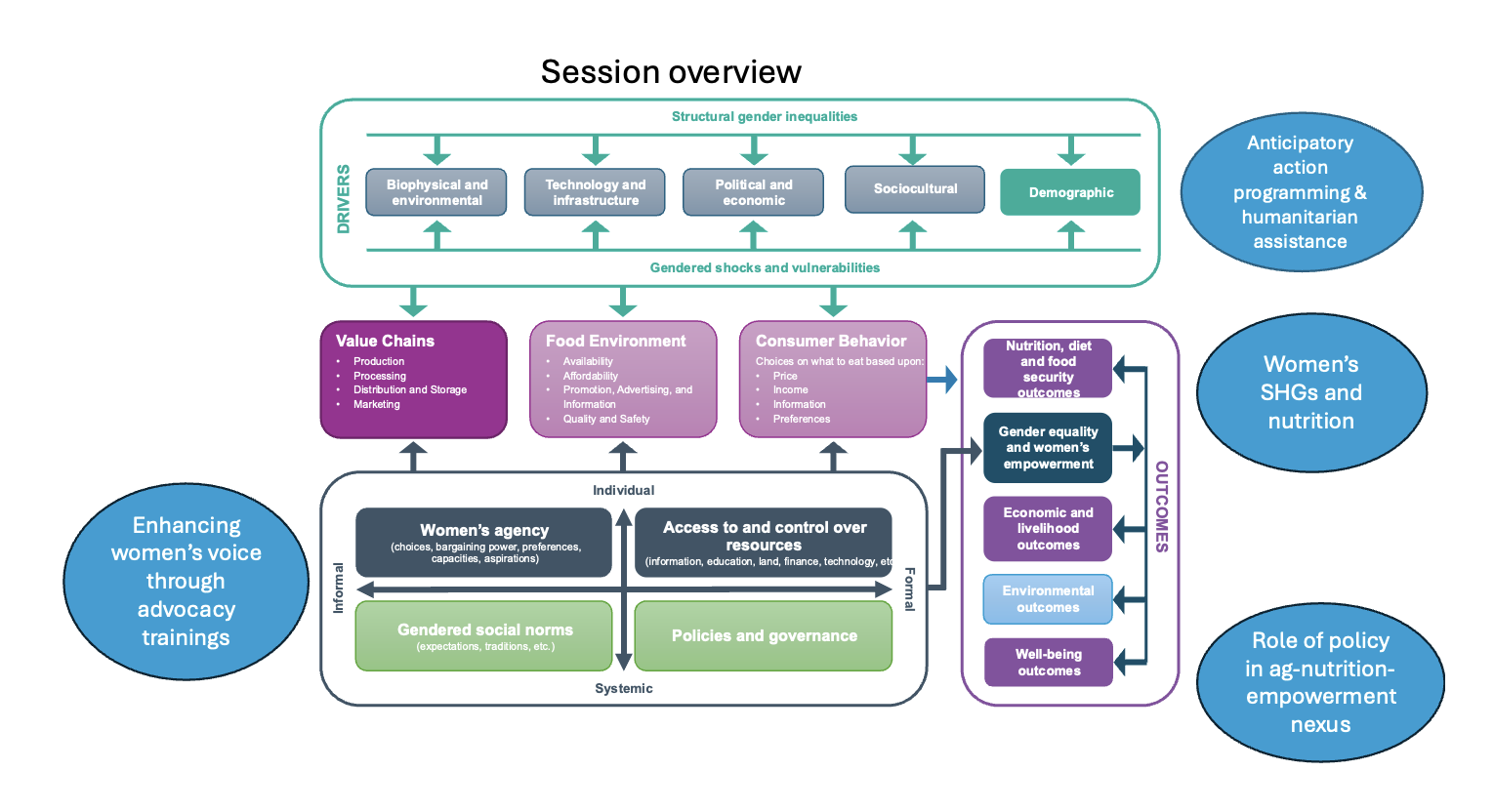

Women in fragile- and conflict-afflicted settings have especially acute vulnerabilities. The 2021 UN Food Systems Summit Gender and Food Systems Framework shows how food system drivers are anchored in a gendered social, political, institutional, and economic system with structural gender inequalities that shape individuals’ and households’ risks and vulnerabilities. These drivers in turn influence the three main components of food systems—value chains, food environments, consumer behavior—and their outcomes, including nutrition, diet and food security, gender equality and women’s empowerment, economic and livelihood outcomes, environmental outcomes, and well-being outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The NGO Forum event focused on several types of programs aimed at increasing women’s empowerment in food systems: Women’s self-help groups (SHGs) in India; anticipatory action programming and humanitarian assistance in Nigeria and Nepal; trainings aimed at building communication and advocacy skills in Nigeria; and broader efforts to measure and map out an agenda for improving women’ voice in the policymaking process for both agriculture and nutrition.

Women’s self-help groups and nutrition in India

Agnes Quisumbing, IFPRI Senior Research Fellow, presented work synthesizing findings from impact evaluations of two programs implemented by SHG platforms in India and a value-chain program implemented by the Aga Khan Foundation.

The first two, the JEEViKA Multiple-Convergence Pilot and the Professional Assistance for Development Action (PRADAN) Nutrition Intensification Model, were proof-of-concept pilot interventions that provided health and nutrition behavior change communication on maternal and child nutrition through dedicated frontline workers. The first was offered in the state of Bihar, and the second in five states in central and eastern India.

The JEEViKA pilot worked with government and other stakeholders to coordinate service delivery to households; nutrition messages were delivered directly to mothers of infants and young children during SHG meetings. In the PRADAN program, nutrition was integrated into their main program on agricultural production and community women were trained to provide nutrition messages about better diets to SHG members.

Project Mesha aimed to improve the lives of women members through productivity improvements in the goat value chain. It established an entrepreneurial cadre of women community-based para-vets (Pashu Sakhis) to provide preventive health services to goat flocks but did not have an explicit nutrition focus.

IFPRI research found that while none of the programs impacted anthropometric outcomes, all improved diets—even Project Mesha, despite its lack of a nutrition focus. Tracking the effects of these SHG-based programs using the pathways to impact framework, the researchers found that the PRADAN intervention activated the income and agriculture pathways, as evidenced by higher per capita food expenditure and knowledge and use of kitchen gardens. The JEEViKA pilot activated the agriculture pathways, also through kitchen gardens, the behavior change communication pathway (by increasing knowledge), and the rights pathway, through awareness of government services linked to health and nutrition.

Project Mesha activated the income pathway by increasing income from healthier goat herds and income for the frontline workers delivering veterinary services, the agriculture pathway (through home gardens), and the women’s empowerment pathways by increasing women’s decision-making on income from productive activities.

Comparing the three programs, there are several important lessons: Early complementary investments and buy-in from communities are needed; design features should be aligned with intervention objectives, particularly addressing income constraints and targeting the right age group; incentives must be used judiciously to motivate frontline workers; and programs should be delivered at appropriate intensity over a sufficiently long time period to realize change.

Gender-responsive anticipatory action programming

Jordan Kyle, IFPRI Research Fellow, shared findings from research conducted in Nepal and Nigeria examining how anticipatory action (AA) programming—which provides support to vulnerable households ahead of predicted disasters—can better serve women and girls. Women and girls face disproportionate risks from extreme weather and other types of disasters and crises and experience more limited recovery prospects in their wake. The study used data from key informant interviews and focus group discussions with stakeholders, including government agencies, NGOs, local advocacy groups, and direct beneficiaries of flood programs, to identify how to better support women through AA.

Specifically, researchers used the Reach-Benefit-Empower-Transform (RBET) framework developed by IFPRI and partners to identify practical ways to design more gender-responsive AA programs—from diversifying early warning communication channels and registering vulnerable individuals (not just households) for AA programs, to aligning benefits with women’s needs and preferences, including them in program design, and providing training to strengthen their leadership in disaster preparedness. The research also highlighted the importance of engaging men and community leaders to challenge restrictive gender norms. With disasters growing more frequent and severe, these strategies offer actionable guidance for policymakers and practitioners to shift from gender-blind relief to transformative, inclusive preparedness.

Women’s leadership and advocacy trainings

Katrina Kosec, IFPRI Senior Research Fellow, presented findings from a randomized control trial in South West Nigeria assessing the impacts of a training program on women’s political and economic empowerment. The program had two main elements: An advocacy and leadership training for women and training in male allyship for women’s husbands. A control group received no trainings, the first treatment group received only women’s trainings, and the second treatment group received both women’s and husbands’ trainings.

The results were powerful. Women who received the training were significantly more likely to attend community meetings, speak up in those meetings, and engage their leaders directly—both one-on-one and in public forums. They also reported greater confidence, greater ability to depend on other women for support, and a deeper understanding of how to influence local decision-making. Crucially, they were more likely to perceive their leaders as responsive to the issues they raised.

The positive outcomes went beyond political voice. Trained women were also more likely to apply for community grants, take the lead on grant applications, engage in income-generating activities outside the home, save with the intention of investing in a business, and experiment with new crops or varieties. In other words, the training helped build not only civic engagement and policymaker responsiveness to women but also women’s economic participation and resilience.

The study offers key policy lessons. First, women’s political voice can be strengthened through relatively low-cost, light-touch interventions—when women are given the tools, space, and support, they engage. Second, women’s voice and confidence can unlock economic opportunities—civic and economic empowerment go hand in hand. Third, treating women as change agents, rather than passive beneficiaries, is critical. This training didn’t deliver resources, it built agency—and women used that agency to access resources and reshape decisions in their communities. Fourth, group-based learning works. It created not just skills, but solidarity and sustained support systems. And finally, rigorous evaluation matters. It helps identify what works, for whom, and why—so we can design smarter programs that leave no one behind. This is especially critical for supporting gender equity in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

Women’s Empowerment in Agrifood Governance (WEAGov)

Catherine Ragasa, IFPRI Senior Research Fellow, focused on the role of policy in achieving multiple development goals and “impacts at scale” for women’s empowerment. Diverse perspectives, equal participation, and credible data and evidence are needed for sound policy and investment choices. The Women’s Empowerment in Agrifood Governance (WEAGov) assessment framework, developed by IFPRI and partners, is a new tool to help measure and track progress in gender consideration, women’s inclusion, and women’s leadership in each stage of agrifood policy—design, implementation, and evaluation.

WEAGov pilot studies in India and Nigeria have yielded three important lessons. First, while Nigeria has passed its National Gender Policy in Agriculture, and is applauded as unique in the region in addressing these issues, the policy has largely been underfunded and weakly monitored—suggesting that efforts should focus not just on policy design but on funding and evaluation and on working with implementing agencies, especially the Ministry of Budget and Finance, early on.

Second, while India has been applauded for institutionalizing a gender-responsive budgeting process, two decades of implementation show that it has become an exercise focused more on filling in numbers than meeting concrete goals. The current gender budget statement lacks strategic direction and will likely have only a limited impact on addressing gender inequalities, the study suggests. The WEAGov assessment for India highlights the need to implement a comprehensive strategy that includes careful in-depth gender analysis; collecting, analyzing, and publicizing gender-disaggregated data; greater recognition of women as farmers and key value chain actors; and identification of priority action areas based on known major gender gaps; and integrating these data into the budgeting process.

Last, while agrifood policies in both countries strongly consider gender and many initiatives have been implemented to strengthen women’s land rights, the studies show that these policies have limited effectiveness. Reasons include a lack of proper implementation, prevailing social attitudes, and a general lack of education and awareness of these policies and legal rights. The WEAGov assessment highlights the need to create greater awareness through community involvement and educating both rural women and men—making them aware of women’s land rights, important provisions in policies and laws, and opportunities to provide feedback.

The path forward

Across these diverse programs and geographies, a common thread emerges: Empowering women in fragile food systems requires more than isolated interventions—it demands intentional design, local buy-in, sustained support, and policy environments that translate gender commitments into action.

Fragile settings—characterized by weak institutions, limited service delivery, and heightened exposure to shocks—can amplify the risks women face, but also the transformative potential of inclusive programming. Whether through self-help groups, anticipatory action, advocacy trainings, or improved governance, investing in women’s agency and inclusion delivers dividends across food, health, and governance outcomes. As global challenges intensify, these lessons offer a roadmap for building more resilient, equitable food systems—from the ground up.

Agnes Quisumbing is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Gender, and Inclusion (PGI) Unit; Katrina Kosec is a PGI Senior Research Fellow; Jordan Kyle is a PGI Research Fellow; Catherine Ragasa is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Innovation Policy and Scaling Unit. Opinions are the authors’.

Thanks to Sarah Pechtl and Isabel Lambrecht for their work organizing the panel.

This work was supported by the CGIAR Science Program on Food Frontiers and Security and the CGIAR GENDER Accelerator.

Related news

-

NATURE+ circular bioeconomy activities reach more than 5,000 people

CGIAR Initiative on Nature-Positive Solutions16.04.25-

Environmental health & biodiversity

-

Gender equality, youth & social inclusion

By 2024, the NATURE+ Initiative’s circular bioeconomy activity reached dozens of communities in fi…

Read more -

-

Breaking Barriers: A journey of transformation towards gender equality

The Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)11.04.25-

Gender equality, youth & social inclusion

Through training delivered in collaboration with partners—including ‘Union Pour L’emancipatio…

Read more -

-

Empowering women through food innovation

International Potato Center (CIP)04.04.25-

Gender equality, youth & social inclusion

In Fort Dauphin, in the south of Madagascar, a group of ten courageous and determined…

Read more -