‘Alt meats’ are not the answer for poorer countries

- From

-

Published on

18.09.19

- Impact Area

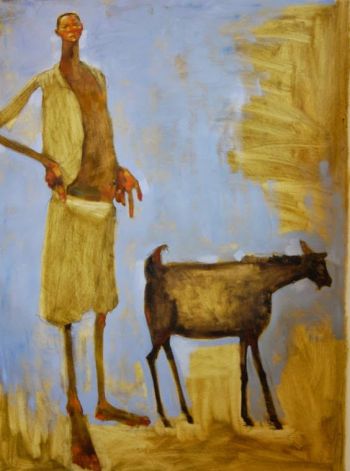

All paintings by Olivia Pendergast, an American artist living and working in Kenya.

This opinion piece, published this week in the Financial Times, is written by Isabelle Baltenweck, an agricultural economist leading the Policies, Institutions and Livelihoods program at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI).

It is time we recognized the vital role livestock plays across the world’s developing economies

Excitement about alternative meat and dairy products is exploding. Lab-grown or plant-based, animal-free substitutes are being held up as a panacea to overcome the negative environmental and health impacts associated with the world’s livestock systems.

But that assumption rests on the skewed perspectives of North Americans and western Europeans—and misses a big part of the story.

In many developing countries and less affluent economies, animal-source food is less a consumer product than a vital source of income, food and livelihood.

For the one in 10 people living on less than $2 a day, ‘alt-meats’ are unlikely to be a viable dietary solution for the simple reason that most people would be unable to access or afford them.

Maasai Man I, by Olivia Pendergast

Samburu livestock herders in northern Kenya, for example, live in rural areas with little access to grocery stores that might sell plant-based meat or soy milk. Instead, they rely on their cows, goats and sheep for both food and income.

Meat and dairy alternatives do little to address the nutritional challenges faced by the poor in Africa and Asia.

The most common diet-related health problem there is not overconsumption of animal-source foods but ‘hidden hunger’, a form of malnutrition characterized by deficiencies in the essential nutrients found in milk, meat and eggs.

For the impoverished Ethiopian or Bangladeshi mother who is unable to breastfeed her newborn because she is herself malnourished, even the smallest gains in milk, meat or egg consumption can be vital.

Woman with New Baby—Kibera, by Olivia Pendergast

According to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, just 20 grammes of animal protein per person per day—the equivalent of one and a half eggs—can stave off malnutrition.

Getting enough protein and micronutrients is especially important for vulnerable groups such as infants and children, mothers, the sick and the elderly. For babies between six and nine months in Cotopaxi, rural Ecuador, for example, eating an egg a day meant stunting was reduced by almost 50 per cent. One mother told us her baby had started standing by himself and became more engaged after she added eggs to his diet.

Equally important are livestock’s contributions to the rural economy—a feature under-appreciated by those in more industrialized countries. In low to middle-income countries, livestock is a lifeline as well as financial asset, providing jobs, incomes, financial collateral, insurance, fertilization for croplands and muscle to transport farm goods.

My colleague Jacob Mignouna, a senior scientist, owes his education to the chickens his mother sold at their local market in Togo to pay for his and his sisters’ school fees. Without chickens, his life would have taken a different course.

Livestock can be the main, or only, economic option available to poor households. Growing crops in drought-prone environments such as the Sahel is, where not impossible or environmentally damaging, risky, tedious and often unproductive.

Pregnant Mother—Kawangare, by Olivia Pendergast

Unlike planted crops, animals can be moved from place to place in search of forage and water, a crucial advantage as global temperatures rise.

All of these practical benefits—nutritional, economic and environmental—make livestock indispensable.

It is time we worked with, not against, the world’s many livestock systems. To begin with, this means recognizing the vital role farmed animals play across all of the world’s developing economies.

The good news is that we already have the research needed to help livestock-keeping communities be more efficient and sustainable as well as profitable. Such research is helping to reduce livestock emissions through better feed and care, cut livestock losses from severe droughts through insurance schemes and empower millions of women.

Rather than trying to replace all of the world’s meat, milk and eggs with alternatives, we should be improving husbandry systems and protecting these living assets for the most vulnerable.

Read this article on the Financial Times website: Alternative meat products are not the answer for poorer countries, 16 Sep 2019.

![]()

Related news

-

IRRI and ICRISAT Set a Joint Vision to demonstrate Integrated Seed Systems for Dryland Farming in South Asia

International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT)25.04.25-

Food security

CGIAR centers align efforts to drive inclusive, impact-oriented research from 2025 to 2027 New Delhi…

Read more -

-

Unveiling a new vision for animal breeding in Africa

International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)16.04.25-

Food security

The African Animal Breeding Network (AABNet), a new platform for animal breeding professionals to ad…

Read more -

-

Fostering collaboration and knowledge sharing in digital agriculture

International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI)16.04.25-

Food security

Stronger institutional partnerships and knowledge co-creation will accelerate the digital agricultur…

Read more -